One of Nesta’s annual predictions made in December 2019 was an outbreak of Monty Python-style silly walks to counter gait identification, or surveillance that identifies people based on how someone walks. Nesta's Explorations Initiatives funded my short experiment to investigate and demonstrate the science behind tracking how people walk.

Monty Python’s "Ministry of Silly Walks" was a satire on bureaucratic inefficiency, first aired on the BBC in 1970. Unless you work at the Ministry of Silly Walks, silly walking is not meant to be taken seriously. But is it possible to measure a silly walk, and practically how would we go about doing it?

I tested how off-the-shelf software and hardware can be used to accurately measure and detect silly walks. The goal is to encourage readers to re-engage with silly walks in a fun and new way, and realise the trade-offs one makes when reckoning with emerging technologies.

Roots of motion capture

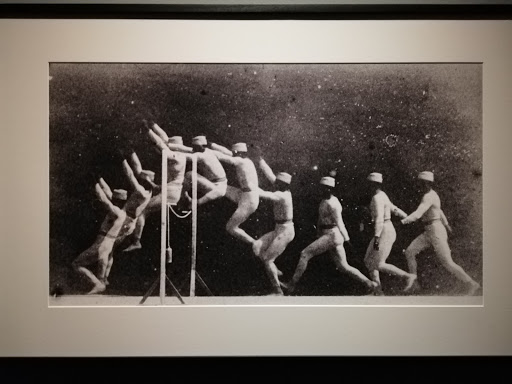

While we may think motion capture is a relatively recent innovation -- maybe associating it with green suits and visual effects from our favourite films -- the principles of motion capture can be traced much further back.

In 1878, photographer Eadweard Muybridge set up an experiment: using thin threads that easily broke to trigger camera shutters (to settle an argument on whether all hooves go off the ground when a horse gallops). Later, French doctor Étienne-Jules Marey invented a ‘photographic gun’ that captures a range of movement by people and animals. So the practice of measuring ourselves in motion is really not new at all. We just have increasingly interesting ways of, and reasons for, doing it.

Measuring silly walks

Next, I apply a data science lens to the very serious topic of silly walking, using a method called pose estimation. It estimates where key body joints are in images and videos, analogous to drawing stick figures over limbs. Accuracy varies by filming conditions and parameters: there may be false positives due to clutter or false negatives due to occlusion. On its own, pose estimation does not recognise or identify people.

I tried integrating various tools for skeletal tracking and pose estimation. These include open-source solutions like OpenPose as well as commercial offerings like Cubemos and Nuitrack. This is a demo of a real-time 3D skeletal tracking SDK integrated in Unity: since I used a depth camera (Intel Realsense D415), which provides an additional channel, there are fewer dropped detections than by using just RGB information.

Finally, it is silly walking time: I trained a PoseNet model to identify three poses: standing, raising left knee and raising right knee. Data collection was done with a webcam and under 20 images for each class. The result is shown in the following video, with probability scores (0-1) shown next to predictions for the respective poses.

The verdict

This quick experiment shows that tools can be quite easily integrated to measure and detect how we walk, to varying degrees of success and silliness. But is there cause for concern around mass surveillance based on how we walk?

To re-identify a person based solely on the way we walk is no small feat. Outside a laboratory setting, gait identification is not as widely deployed as facial recognition. But the possibility for identification becomes higher when combined with sensor data (e.g. in smart clothing or walking surfaces), as well as features alongside walking pose, which, in some cases, can be intrusive and creepy if lacking informed consent over how data is being collected and used.

But there are also scalable and useful applications. Pose estimation and related research has been deployed in tools that are used in applications from fall monitoring in hospitals, identifying Parkinsonain gait, and home-based physical therapy to the modelling of clothes in online shopping, correcting yoga poses, touch-free art, and synthesizing dance moves from music.

Perhaps our best defence is more critical thinking around newer technologies, prioritising ethics in the deployment of tools and funding of products, and regulatory oversight.